First, I visited the department for women.

Every patient tried to shout louder than the previous one and tell what worries them more:

-“We are happy to see you – let them write and know!”

-“Look at the room we live in – they cannot even paint the walls and repair the floor!”

-“They don’t see us as people!”

-“Our pension is 400 rubles and it is not enough to buy medicine.”

-“We need water – a little elementary thing.”

-“No water, no electricity. How can we live here?”

-“Look, look…We live in flourishing Abkhazia, flourishing Abkhazia!”

The doctor’s voice yelled –”Stop it!”

The woman takes her seat –”I am silent,” – she said with a sarcastic smile.

-“If we are shown somewhere, maybe they’ll repair the hospital and give a normal pension to … the disabled.”

-“What can we do? Who are we to plead our claim to?”

-“We are here like those ones…”

-“Go on, you said you are going to sing.”

A middle-aged woman dressed in a few jackets and tightly tied by two kerchiefs (it is quite cold in the room) is singing with a heart-rending, sometimes hysterical but still beautiful voice:

“-Oh, raspberry, berry,

It tempted us,

It invited us!”

Everybody sings with her in their own manner and at different times.

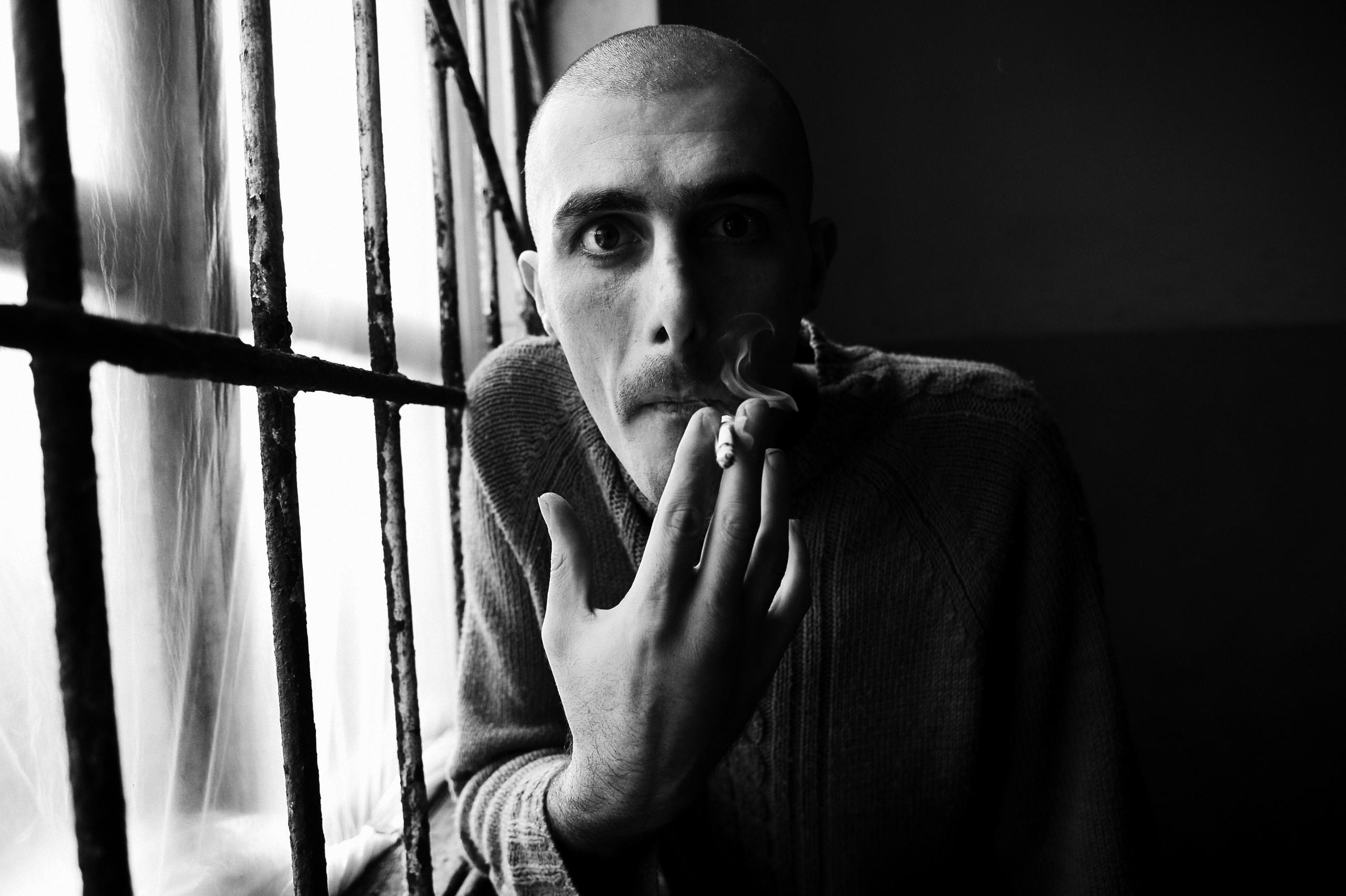

The iron grate is opening again in the men’s department before me:

Doctor: “So, have you taken a photo of Romochka? You are so beautiful, well dressed. Raise your hand. Let’s see, let’s see how long he can hold. And this is Felix – our God’s man.”

In a few minutes, the doctor goes back to Romochka: “Stop, stop, put your hand down.”

I enter the next chamber. The doctor says: “Here are the guests” in a gentle, sweet voice.”

I can hear inarticulate sounds, mumbling, and whispering.

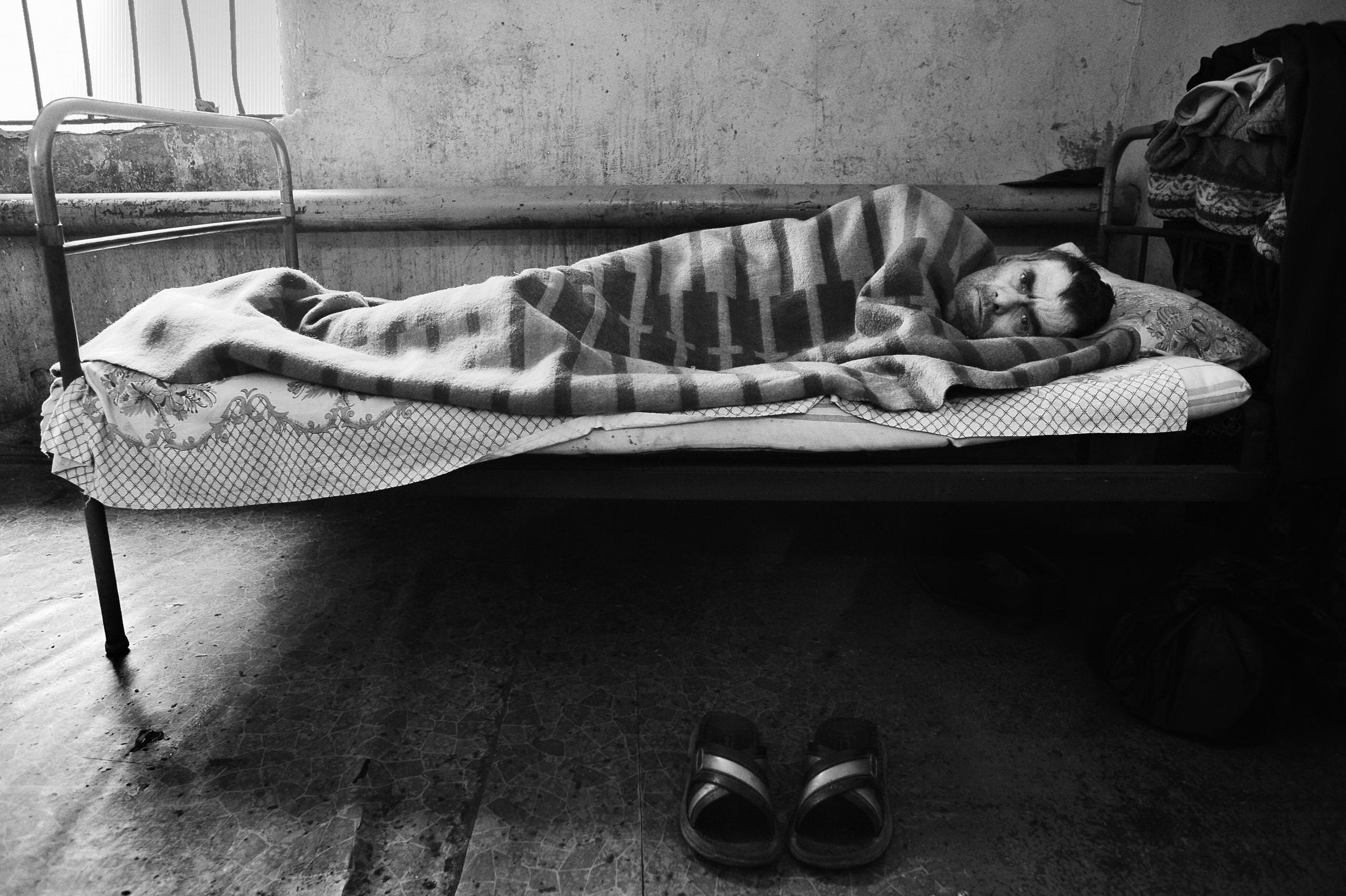

Some of the patients are hiding under a torn blanket and use a hole to watch what is happening.

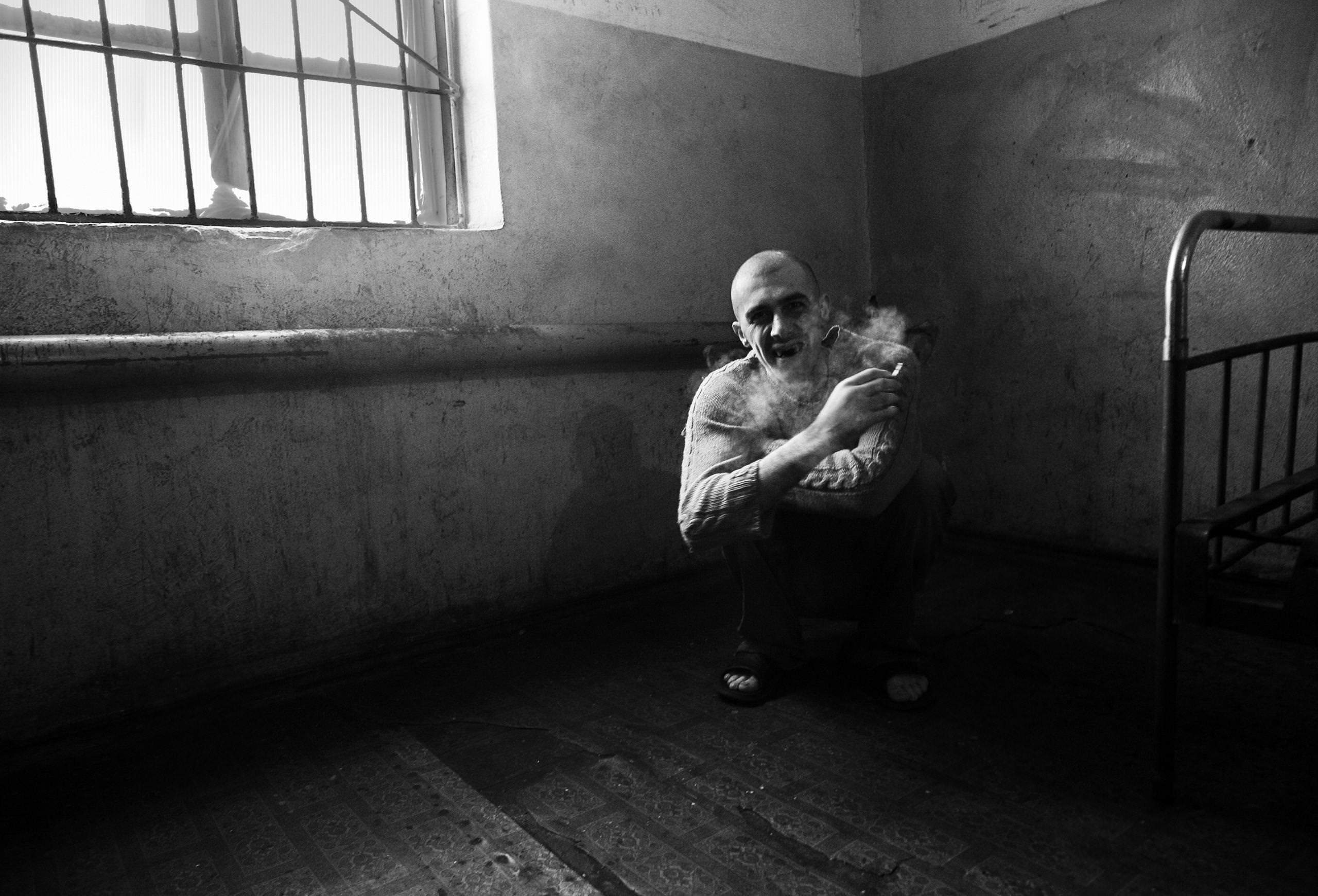

One of the patients is standing at the window closed by black grates, gesturing actively and reading some script in a language that no one knows.

The bald-shaven man is sitting in the corner and striking himself on the head without stopping as a nurse is enters with pills in a box.

Everybody is pushing me closer to the grate, unarticulated sounds now reminding me of gurgling and not stopping. Only when a huge key turns in a large, rusty lock does everything quiet down.

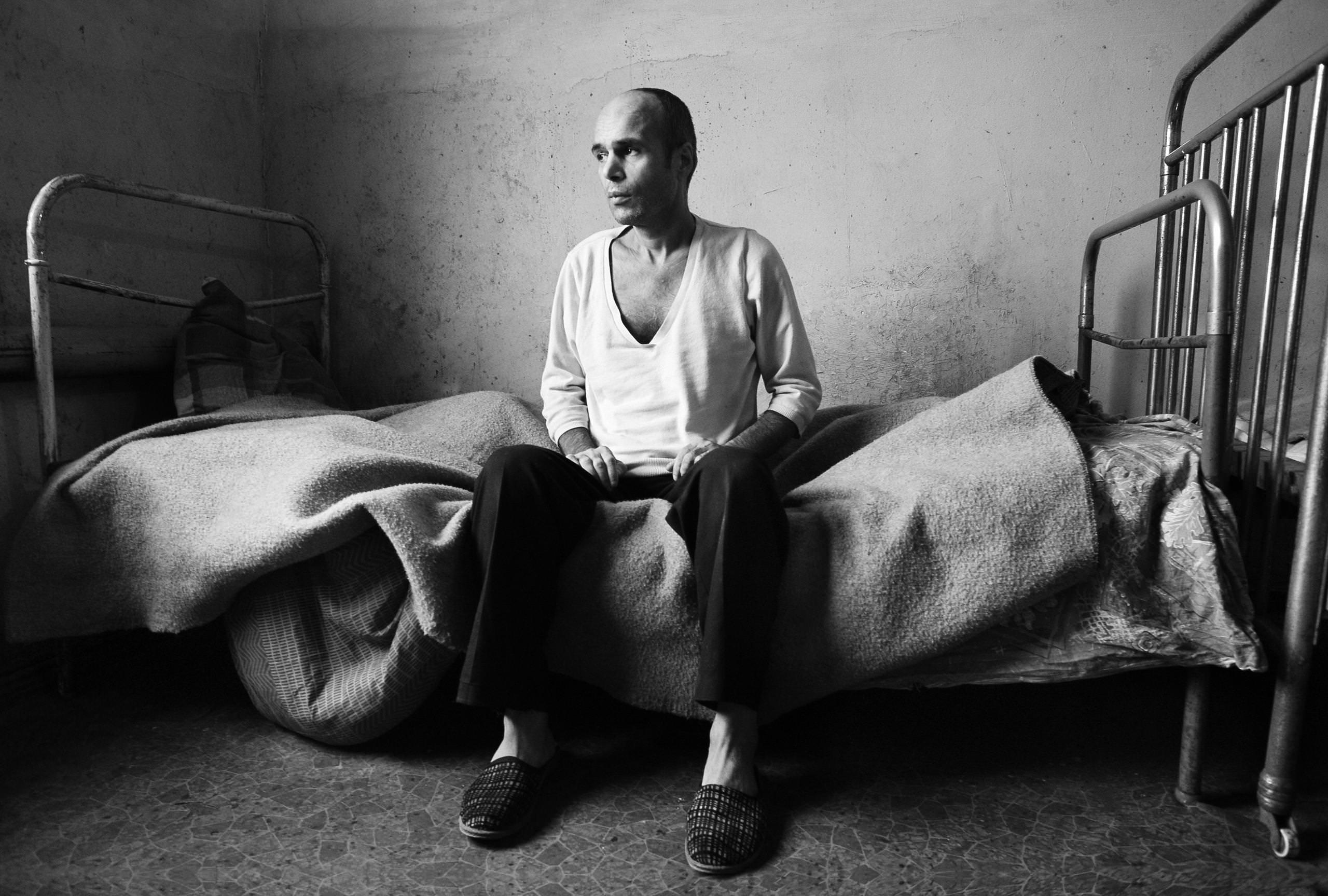

Now I find myself in a “privileged patient’s chamber”.

This room is a little bigger than the others. The walls are the same cold concrete but not shabby and painted gray. There is an odd-shaped heater in the room to get warm. On the wooden tables there are haphazard places fruits next to pulp fiction about killers and women’s detectives. Near the bed there is a huge Bible decorated with dark glasses that possibly could serve as a bookmark.

Icons, microphones, and deodorants are scattered on little tables and chairs that we usually see in kindergartens.

The doctor says about the patient:

-“He is so precise, pedantic. He is very accurate. Actually he is a little bit of a privileged patient. His mother serves in the church. That’s why…

Then he is quiet and safe.

Have you already spent a year here?”

The patient is ready to answer:

“Yes, it will be one year on the 18th.”

Then he is telling his story :

“We came to Moscow with my mom. I was about 10, and when my mother went to the shop, I went for a walk. It was at Baumanskaya.

So, I walked and saw a little basement with a glass-blower’s shop. I entered there. They were blowing the glass and laughed at something.

I stopped and looked at them continuously for a long time. They seemed not to notice me.

I went out, and then my mother came. I told her: “Mum, there was a glass-blower’s shop, let’s go, I will show you”.

We came there and saw that there was no building. No building…

I was about 10.

I couldn’t find this place anymore or it didn’t exist.

I said, mum, there was a glass-blower’s shop, I was there, I was in the basement. Mother said: “You might have imagined” – “No, I haven’t”.